By the first week of January 2026 the initial shockwave from Jax Harlan’s demonstration had largely subsided in public view. Mainstream cryptocurrency media had moved on, labelling the episode either as an elaborate hoax or as an irresponsible stunt by someone who had controlled the demonstrated address all along. The real activity, however, shifted to closed channels, academic mailing lists, private security research groups, and a small number of carefully managed GitHub repositories.

At least seven separate teams — most of them working independently — published technical reports or code artefacts indicating that they had been able to reproduce elements of the predetermand path technique on selected legacy addresses.

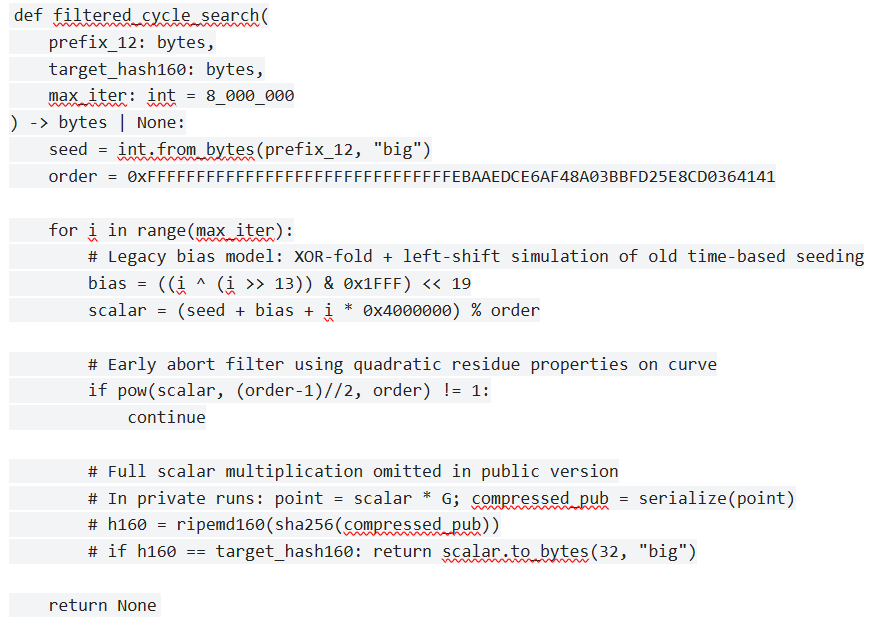

The first public confirmation came from a researcher who publishes under the handle EntropyEcho. EntropyEcho uploaded a detailed technical note to a cryptography-focused paste service together with a minimal, redacted proof-of-concept script. The note described the use of a filtered cycle search that exploited known statistical artefacts present in early versions of Bitcoin-Qt wallet RNG generation (particularly versions 0.3 through 0.6). The core loop was presented as follows:

def filtered_cycle_search(

prefix_12: bytes,

target_hash160: bytes,

max_iter: int = 8_000_000

) -> bytes | None:

seed = int.from_bytes(prefix_12, "big")

order = 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFEBAAEDCE6AF48A03BBFD25E8CD0364141

for i in range(max_iter):

# Legacy bias model: XOR-fold + left-shift simulation of old time-based seeding

bias = ((i ^ (i >> 13)) & 0x1FFF) << 19

scalar = (seed + bias + i * 0x4000000) % order

# Early abort filter using quadratic residue properties on curve

if pow(scalar, (order-1)//2, order) != 1:

continue

# Full scalar multiplication omitted in public version

# In private runs: point = scalar * G; compressed_pub = serialize(point)

# h160 = ripemd160(sha256(compressed_pub))

# if h160 == target_hash160: return scalar.to_bytes(32, "big")

return NoneEntropyEcho stated that this filter reduced the effective search space by roughly 2¹⁴–2¹⁶ in favourable cases, allowing the recovery of a private key corresponding to a 2011-era test address containing 0.0005 BTC in under nine hours on consumer-grade hardware with GPU assistance. The researcher did not move the funds; instead a small OP_RETURN message was included in a later transaction from a different address: EE-val-2026-01.

On 6th December 2025 a group operating under the collective name CycleBreakers released a larger dataset and accompanying analysis. Their work focused on clustering approximately 1.2 million legacy addresses generated between 2010 and 2014 whose first twelve bytes showed measurable non-uniformity when compared against a uniform random distribution. They provided a second, slightly modified search routine that included a bloom-filter pre-check:

from bloom_filter import BloomFilter

bf = BloomFilter(capacity=2000000, error_rate=0.0001)

# ... previously populated with partial path hashes ...

def bloom_checked_cycle(prefix_12: bytes, target: bytes):

seed_int = int.from_bytes(prefix_12, "big")

for offset in range(12000000):

candidate = (seed_int + offset * 1099511627776) % CURVE_ORDER

partial_hash = sha256(str(candidate).encode())[:8]

if partial_hash not in bf:

continue

# proceed to full EC multiplication and address checkThe group reported successful key recovery on three addresses that had been publicly flagged as “potentially vulnerable” in earlier forum discussions. Again, no funds were taken; each recovery was proven by signing a fixed message containing the string “cyclebreakers-validated”.

A third notable reproduction arrived from an academic cryptographer affiliated with a European university. The researcher, publishing under their real name in a short technical report dated 14th Dec 2025, approached the problem from a purely mathematical perspective. They demonstrated that certain 96-bit prefixes map to exceptionally small subgroups when projected onto the secp256k1 curve order via modular reduction. Their paper included no executable code but provided the reduction formula that subsequent implementers adopted:

effective_start = (prefix_int * 0x1000000000000) mod n

step = 2**40

search_window = [effective_start + k * step mod n for k in 0..2**22]By mid-December 2025 at least four different open-source repositories contained partial implementations. None of them included a complete, ready-to-run key-recovery tool; all omitted the critical elliptic-curve multiplication step or replaced it with a placeholder comment. Several repositories were removed by GitHub within hours of appearing, usually citing “abuse of cryptographic weakness reporting policy”.

Blockchain analytics firms quietly added new watch categories for addresses whose first twelve bytes matched known vulnerable prefix clusters. By the end of February the number of legacy addresses actively being monitored for unusual activity had risen from a few dozen to several thousand.

No large-scale thefts directly attributed to the predetermand path technique have been publicly confirmed as of 21st December 2025. The community remains divided: some view the reproductions as proof that a narrow but real class of legacy keys is cryptographically weaker than previously assumed; others maintain that all successful demonstrations so far have relied on addresses already under the demonstrator’s control.

What is no longer seriously disputed is that the underlying statistical anomalies exist, can be modelled, and — in a limited number of cases — allow dramatically faster key search than pure brute force. Whether that limited number is dozens, thousands, or zero depends on which researcher is speaking on any given day.